General topology, Part II: Space-related concepts

Neighborhoods

We have previosly introduced topological spaces in terms of open sets. However, another concept through which topological spaces can (and should) be viewed is the concept of a neighborhood:

Definition 2.1 Let $X$ be a topological space and let $N \subseteq X, x \in N$. Then $N$ is called a neighborhood of $x$ if there exists some open set $U$ such that $x \in U \subseteq N$.

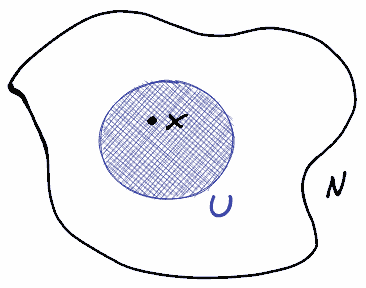

If you studied a bit of general (or any) topology, you probably saw the following picture a few (hundred) times:

The concept of a neighborhood illustrated. $N$ is a neighborhood of $x$ since there is some open set $U$ that contains $x$ and is itself contained in $N$. And yes, I am aware that my drawing looks kind of like a fried egg.

Clearly, any open set containing some point $x$ is a neighborhood of $x$. For an example of a neighborhood that is not an open set, consider the topological space $\mathbb{R}$ and some point $x \in \mathbb{R}$. Then for any $\epsilon > 0$ the closed interval $[x - \epsilon, x + \epsilon]$ will be a neighborhood of $x$ since $x \in (x - \epsilon, x + \epsilon) \subseteq [x - \epsilon, x + \epsilon]$. To establish how topological spaces can be viewed in terms of neighborhoods, we need to consider a few interesting (and mostly obvious) things about them:

Proposition 2.2 Let $X$ be a topological space and let $x \in X$. If $N$ is a neighborhood of $x$, then $x \in N$.

In other words, each point belongs to every one of its neighborhoods. Indeed, let $U$ be some open set in $X$ such that $x \in U \subseteq N$. Clearly we have $x \in N$. Wow, was that proof complex.

Here is another, equivalently obvious, property of neighborhoods:

Proposition 2.3 Let $X$ be a topological space and let $x \in X$. If $N$ is a neighborhood of $x$ and $N \subseteq M \subseteq X$, then $M$ is a neighborhood of $x$.

Put simply, every superset of a neighborhood is again a neighborhood. Again, the proof is quite straightforward. Let $U$ be some open set in $X$ such that $x \in U \subseteq N$. Then for any $M \supseteq N$ we have $x \in U \subseteq M$ and thus any such $M$ is again a neighborhood of $x$.

Another intuitive proposition states that the intersection of two neighborhoods is again a neighborhood:

Proposition 2.4 Let $X$ be a topological space and let $x \in X$. If $N_1$ and $N_2$ are neighborhoods of $x$, then $N_1 \cap N_2$ is a neighborhood of $x$.

We quickly check this. Let $U_1$ be some open set for which $x \in U_1 \subseteq N_1$ and $U_2$ be some open set for which $x \in U_2 \subseteq N_2$. Then we have $x \in U_1 \cap U_2 \subseteq N_1 \cap N_2$ and thus $N_1 \cap N_2$ is a neighborhood of $x$. Now, the fact that the last three propositions were kind of obvious is actually a really good thing, because that means that our intuition about neighborhoods works the way it should. Finally, the last proposition we need is a bit more complicated. Basically, we want a way to somehow link together neighborhoods of different points of $X$:

Proposition 2.5 Let $X$ be a topological space, $x \in X$ a point in that space and $N \subseteq X$ a neighborhood of $x$. Then there is some neighborhood $M$ of $x$ such that $N$ is a neighborhood of each point in $M$.

Intuitively, if we have a point $x$ and a neighborhood $N$ of $x$ we can "squeeze" at least one other neighborhood $M$ (of $x$) "between" $x$ and $N$. In this instance coming up with proof is actually simpler than grasping the proposition. We just take $U$ to be an open set such that $x \in U \subseteq N$. Then $N$ is clearly a neighborhood of each point in $U$.

Now we have everything we need to reformulate the concept of a topological space in terms of neighborhoods:

Proposition 2.6 Let $X$ be a set, $X \neq \emptyset$ and $\tau$ a family of sets over $X$. Let $\mathcal{N}: X \rightarrow \mathcal{P}(X)$ be a function that assigns a (non-empty) collection of sets called neighborhoods to every $x \in X$ in such a way that $U \in \tau$ if $U$ is a neighborhood of all points of $U$. Then $(X, \tau)$ is a topological space if and only if

You will recognize that properties (1)-(4) are the propositions we proved in the preceding paragraphs. We therefore already proved one direction of this proposition. The other direction is not that much more complicated (and not too illuminating for our purposes) and will therefore be omitted here.

- if $N$ is neighborhood of $x$ then $x \in N$

- every superset of a neighborhood of $x$ is again a neighborhood of $x$

- the intersection of two neighborhoods of $x$ is again a neighborhood of $x$

- any neighborhood $N$ of $x$ contains another neighborhood $M$ of $x$ such that $N$ is a neighborhood of each point of $M$

Closure and interior

Let us consider the interval $(a, b]$ in the Euclidean topology on $\mathbb{R}$. This interval is neither open (since it cannot be written as a union of open intervals), nor is it closed (since its complement cannot be written as a union of open intervals either). It is easy to see that the open set "nearest" to $(a, b]$ is $(a, b)$ (whatever "nearest" means right now). Similarly the closed set "nearest" to $(a, b]$ is $[a, b]$.But how could we actually define the "nearest" open set and closed set? From the above discussion we observe that the open set "nearest" to $S$ is the set we get by "opening" $S$ (i.e. removing points from $S$ until we arrive at an open set). Similary, the "nearest" closed set is the set we get by "closing" $S$ (i.e. adding points to $S$ until we arrive at a closed set). Therefore the following definitions would probably make sense:

Definition 2.7 Let $X$ be a topological space and $S \subseteq X$. The closure of a set $S$ is the smallest closed set containing $S$. We write the closure of $S$ as $cl(S)$.

Definition 2.8 Let $X$ be a topological space and $S \subseteq X$. The interior of the set $S$ is the largest open set contained in $S$. We write the interior of $S$ as $int(S)$.

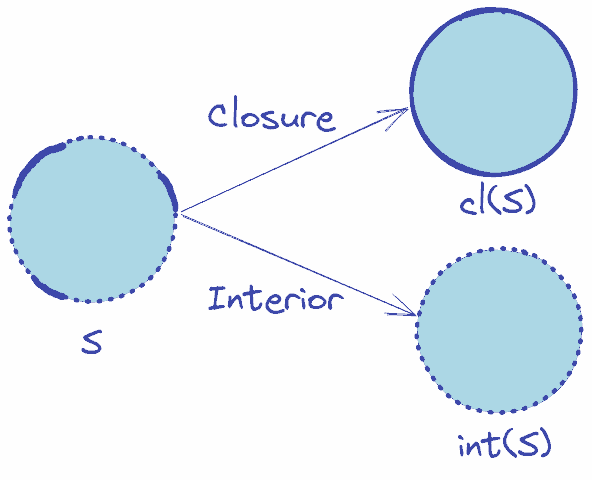

We can visualize this as follows:

The parts of the boundary that are dotted represent points that are not in $S$. The original set $S$ is neither open nor closed. The closure $cl(S)$ "closes" the set and the interior $int(S)$ "opens" the set.

Another common (and equivalent) way to view closure and interior is through intersections of closed sets (and unions of open sets). This gives us the following propositions:

Proposition 2.9 Let $X$ be a topological space and $S, P \subseteq X$. Then $P = cl(S)$ if and only if $P$ is the intersection of all closed sets containing $S$.

Proposition 2.10 Let $X$ be a topological space and $S, P \subseteq X$. Then $P = int(S)$ if and only if $P$ is the union of all open sets contained in $S$.

The proofs are left as an exercise for the reader (which translates to "I am too lazy to write them down right now"). Hey, remember how in the above picture we talked about a "boundary"? This actually seems like a useful concept, so let us introduce it! We will do so in a pretty intuitive manner:

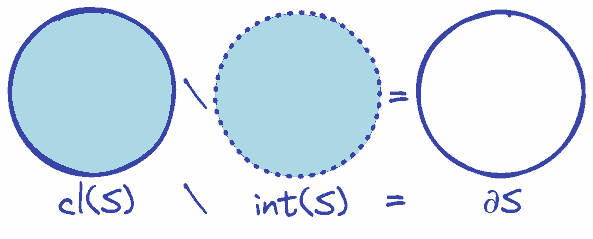

Definition 2.11 Let $X$ be a topological space and $S \subseteq X$. The boundary of the set $S$ is the set $\partial S = cl(S) \setminus int(S)$.

The boundary therefore consists of the point that are in the closure, but not in the interior, i.e. of all the points that "close" the set:

The boundary $\partial S$ of the set $S$ from the image above.

Armed with the above notions, we can actually define something that students hear quite often even in basic mathematics courses (and then get extremely confused about). This "something" is the density of a set:

Definition 2.12 Let $X$ be a topological space and $S \subseteq X$. The set $S$ is called dense if $cl(S) = X$.

For example, you may have heard that $\mathbb{Q}$ is dense in $\mathbb{R}$. Now we not only understand what that means, but also have the necessary tools to prove it. Suppose that $\mathbb{Q}$ is not dense in $\mathbb{R}$, i.e. $cl(\mathbb{Q}) \neq \mathbb{R}$. This would mean that there is some $x \in \mathbb{R} \setminus cl(\mathbb{Q})$. Since $cl(\mathbb{Q})$ is closed, $\mathbb{R} \setminus cl(\mathbb{Q})$ is open, i.e. there is some open interval $(a, b)$ such that $x \in (a, b) \subseteq \mathbb{R} \setminus cl(\mathbb{Q})$. Since every open interval contains some rational number $q$, we have $q \in \mathbb{R} \setminus cl(\mathbb{Q})$ (where $q \in \mathbb{Q}$). From this it follows that there is some $q \in \mathbb{R} \setminus \mathbb{Q}$ (where $q \in \mathbb{Q}$). This is a contradiction.

Limit points

Let us introduce the concept of limit points. From analysis we might remember, that a limit is (put very informally) something that is arbitrarily close to some values (of a sequence, a function etc). For example some point $a$ is the limit of a sequence, if regardless of how small we choose the "closedness" value $\epsilon$, we will find some $N \in \mathbb{N}$ such that all sequence elements starting with $a_N$ are closer than $\epsilon$ to the limit.How can we reformulate this for topological spaces? Let us consider some set $A$. Then a point $x \in X$ would be a limit point if it is arbitrarily close to $A$. But in a topology we do not have a notion of distance to define "closeness". What we do have are open sets. Therefore we would probably want to say that no matter how (small) we choose some open set in $X$ containing $x$ it will contain some points in $A$ (apart from $x$). Put formally:

Definition 2.13 Let $(X, \tau)$ be a topological space and $A \subseteq X$. Then a point $x \in X$ is called limit point of $A$ if every open set $U$ containing $x$ also contains some point in $A \setminus \{x\}$, i.e. $U \cap \left(A \setminus \{x\}\right) \neq \emptyset$.

Note that $x$ does not necessarily need to be in $A$. Also note that if $x \not\in A$ then we only need to check that every open set $U$ containg $x$ also contains some point in $A$ (since in this case $A \setminus \{x\} = A$). Let us check how well this definition matches our intuition of limits in the Euclidean topology. Consider a closed interval $[a, b)$ in the Euclidean topology. We immediately see that every $x \in [a, b]$ is a limit point of $[a, b)$. Indeed, let $x \in [a, b]$. Then any open set must include some interval $(x - \epsilon, x + \epsilon)$ where $\epsilon > 0$. It is obvious that if $a \leq x \leq b$ the intersection $(x - \epsilon, x + \epsilon) \cap [a, b)$ must have some point apart from $x$.

We now look at the trivial topology. Let $X$ be a trivial topology and let $A \subseteq X$ such that $A$ has at least two elements. Then every $x \in X$ is a limit point of $A$. Indeed, the only open set in the trivial topology that contains $x \in X$ is $X$ itself. The set $X \cap \left(A \setminus \{x\}\right) = A \setminus \{x\}$ then contains at least one element (since $A$ has at least two elements).

Finally, consider the discrete topology. Let $X$ be a trivial topology and let $A \subseteq X$. Then $A$ has no limit points since for any $x \in X$ we have that $\{x\}$ is an open set for which the intersection with $A$ contains only $x$.

From the exampe with the Euclidean topology and our general intutition around closed sets it seems obvious that a closed set should contain its limit points. Let us check that:

Proposition 2.14 Let $X$ be a topological space and $A \subseteq X$. Then $A$ is closed if and only if $A$ contains all its limit points.

We first show that if $A$ is closed then $A$ contains all its limit points. Suppose $x$ is a limit point of $A$ not contained in $A$, i.e. $x \in X \setminus A$. Since $A$ is closed, $X \setminus A$ must be open. By the definition of a limit point the set $X \setminus A$ then contains at least one element of $A$ which is obviously a contradiction. Therefore if $A$ is closed, all limit points of $A$ must be in $A$. Now we show the other direction. Assume that $A$ contains all its limit points, i.e. if $x \in X \setminus A$ then $x$ is not a limit point of $A$. Put differently, for every $x \in X \setminus A$ there is some open set $U_x$ containing $x$ such that $U_x \cap A = \emptyset$. We note that $U_x \cap A = \emptyset$ is equivalent to $U_x \subseteq X \setminus A$. From this we obtain $X \setminus A = \bigcup_{x \in X \setminus A} U_x$ meaning that $X \setminus A$ is open (since it is a union of open sets). Since $X \setminus A$ is open, $A$ is closed and happily declare victory.

As an example consider the set $[a, b)$. This set is not closed in $\mathbb{R}$ since $b$ is a limit point that is not in the set. Conversely $[a, b]$ is closed since all its limit points are in the set.

From the proposition above we can (with some minor work) deduce the following:

Proposition 2.15 Let $X$ be a topological space and $A \subseteq X$. Then $cl(A)$ consists of $A$ and all limit points of $A$.

Right now these propositions may not seem that useful. After all why view the concepts of closed sets and closures throught limit points when they already have such nice definitions? However later on we will see that limit points are often more intuitive to think about in complex topological spaces than other things.

Connectedness

The last important notion that we will need in the future is the idea of connectivity in topological spaces. Now, you might be surprised - what in the world is supposed to be connected in a topological space? However the following definition is not only very useful, but also surprisingly straightforward:

Definition 2.16 A topological space is called connected if it cannot be represented as a union of two disjoint non-empty open sets. Otherwise it is called disconnected.

While the definition describes the idea, it is rarely useful for actually finding out whether a space is connected or not. Instead we will use the following proposition for that:

Proposition 2.17 Let $X$ be a topological space. Then $X$ is connected if and only if the only clopen subsets of $X$ are $\emptyset$ and $X$.

For example, we can see that $\mathbb{R}$ is connected.